In Algeria, water shortages left faucets dry, prompting protesters to riot and set tires ablaze.

In Gaza, as people waited for water at a community tap, an Israeli drone fired on them, killing eight.

In Ukraine, Russian rockets slammed into the country’s largest dam, unleashing a plume of fire over the hydroelectric plant and causing widespread blackouts.

These are some of the 420 water-related conflicts researchers documented for 2024 in the latest update of the Pacific Institute’s Water Conflict Chronology, a global database of water-related violence.

The year featured a record number of violent incidents over water around the world, far surpassing the 355 in 2023, continuing a steeply rising trend. The violence more than quadrupled in the last five years.

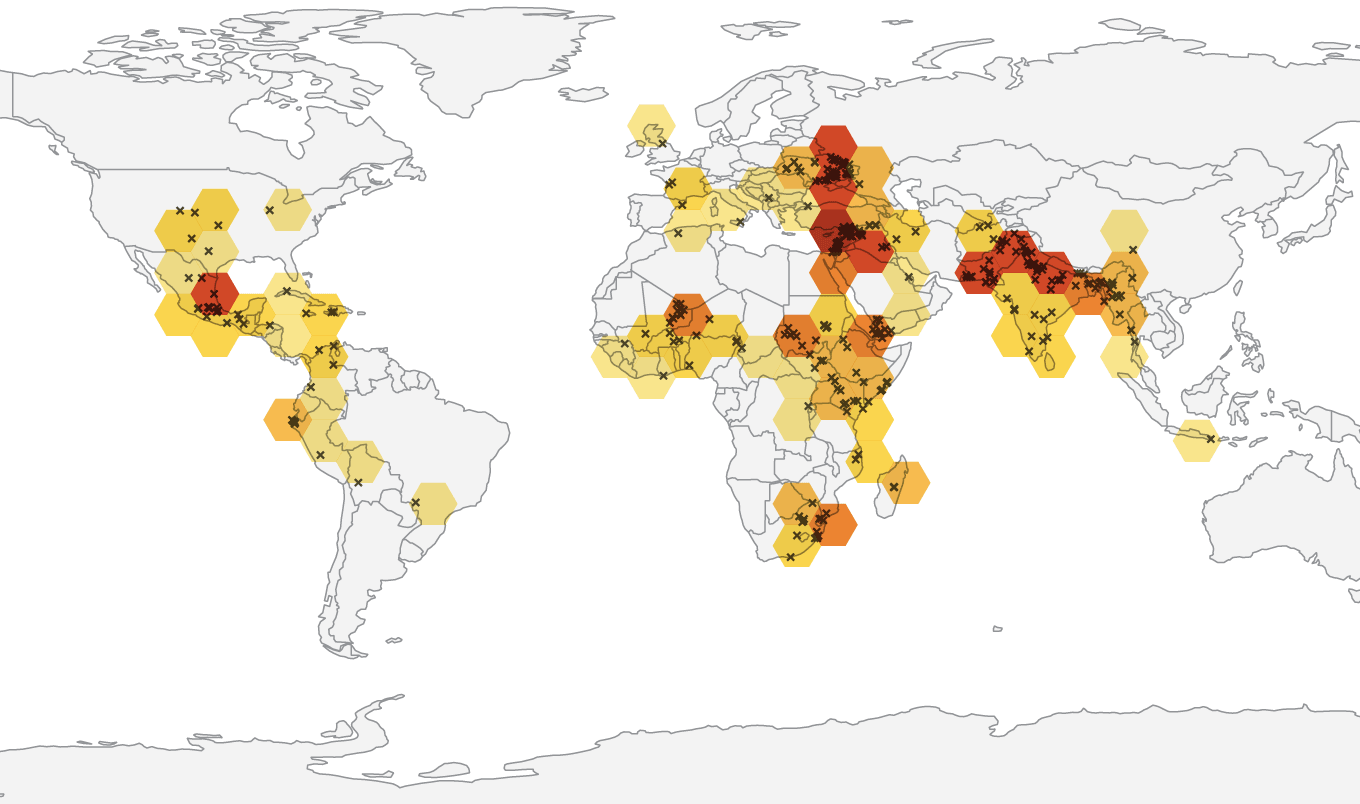

In 2024, there were 420 water-related conflicts globally

The majority of incidents were in the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Eastern Europe.

Conflicts

Russia and Ukraine

51 conflicts

Israel and Palestine

66

3,000 MILES

Russia and Ukraine

51 conflicts

Israel and

Palestine

66

3,000 MILES

Pacific Institute

Sean Greene LOS ANGELES TIMES

The new data from the Oakland-based water think tank show also that drinking water wells, pipes and dams are increasingly coming under attack.

“In almost every region of the world, there is more and more violence being reported over water,” said Peter Gleick, the Pacific Institute’s co-founder and senior fellow, and it “underscores the urgent need for international attention.”

The researchers collect information from news reports and other sources and accounts. They classify it into three categories: instances in which water was a trigger of violence, water systems were targeted and water was a “casualty” of violence, for example when shell fragments hit a water tank.

Not every case involves injuries or deaths but many do.

The region with the most violent incidents was the Middle East, with 138 reported. That included 66 in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, both in Gaza and the West Bank.

In the West Bank there were numerous reports of Israeli settlers destroying water pipelines and tanks and attacking Palestinian farmers.

In Gaza the Israeli military destroyed more than 30 wells in the southern towns of Rafah and Khan Younis.

Gleick noted that when the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Israeli and Hamas leaders last year, accusing them of crimes against humanity, the charges mentioned Israeli military attacks on Gaza water systems.

“It is an acknowledgment that these attacks are violations of international law,” he said. “There ought to be more enforcement of international laws protecting water systems from attacks.”

Water systems also were targeted frequently in the Russia-Ukraine war, in which the researchers tallied 51 violent incidents.

Residents collect water in bottles in Pokrovsk, Ukraine, where repeated Russian shelling has left civilians without functioning infrastructure.

(George Ivanchenko / Associated Press)

Russian strikes disrupted water service in Ukrainian cities, and oil spilled into a river after Russian forces attacked an oil depot.

“These aren’t water wars. These are wars in which water is being used as a weapon or is a casualty of the conflict,” Gleick said.

The researchers also found water scarcity and drought are prompting a growing number of violent conflicts.

“Climate change is making those problems worse,” Gleick said.

Many conflicts were in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

In India, residents angry about water shortages assaulted a city worker.

In Jammu, India, a woman carries a container of drinking water filled from leaking water pipes in March.

(Channi Anand / Associated Press)

In Cameroon, rice farmers clashed with fishers, leaving one dead and three injured.

At a refugee camp in Kenya, three people died in a fight over drinking water.

There’s an increase in conflicts over irrigation, disputes pitting farmers against cities, and violence arising in places where only some water is safe to drink.

A man carries jugs to fetch water from a hole in the sandy riverbed in Makueni County, Kenya in February 2024.

(Brian Inganga / Associated Press)

Gleick, who has been studying water-related violence for more than three decades, said the purpose of the list is to raise awareness and encourage policymakers to act to reduce fighting, bloodshed and turmoil.

The United Nations, in its Sustainable Development Goals, says every person should have access to water and sanitation.

“The failure to do that is inexcusable and it contributes to a lot of misery,” Gleick said. “It contributes to ill health, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, water-related diseases, and it contributes to conflicts over water.”

In Latin America, there were dozens of violent incidents involving water last year.

In the Mexican state of Veracruz, protesters were blocking a road to denounce a pork processing plant, which they accused of using too much water and spewing pollution, when police opened fire, killing two men.

In Honduras, environmental activist Juan López, who had spoken up to protect rivers from mining, was gunned down as he left church. He was the fourth member of his group to be murdered.

A man fills containers with water because of a shortage caused by high temperatures and drought in Veracruz, Mexico in June 2024.

(Felix Marquez / Associated Press)

“There needs to be more attention on this issue, especially at the international level, but at the national level as well,” said Morgan Shimabuku, a senior researcher with the Pacific Institute. “It is getting worse, and we need to turn that tide.”

For 2024, there were few events in the U.S., but among them were cyberattacks on water utilities in Texas and Indiana.

In one, Russian hackers claimed responsibility for tampering with an Indiana wastewater treatment plant. Authorities said the attack caused minimal disruption. In another, a pro-Russian hacktivist group manipulated systems at water facilities in small Texas towns, causing water to overflow.

The Pacific Institute’s database now lists more than 2,750 conflicts. Most have occurred since 2000. The researchers are adding incidents from 2025 as well as previous years.

During extreme drought in Iran worsened by climate change, farmers were desperate enough to go up against security forces, demanding access to river water. Iran’s water crisis, compounded by decades of excessive groundwater pumping, has grown so severe that the president said Tehran no longer can remain the capital and the government will have to move it to another city.

Tensions also have been growing between Iran and Afghanistan over the Helmand River, with Iranian leaders accusing their upstream neighbor of not letting enough water flow into the country.

Gleick said if the drought persists and the Iranian government doesn’t improve how it manages water, “I would expect to see more violence.”