Inside the courtroom of the sprawling Wirecard criminal trial, SoftSwiss founder Ivan Montik was forced into a position he had long avoided: answering under oath. What emerged was not a routine testimony from a software executive. It was a revealing dissection of an ecosystem that prosecutors increasingly see as operating far beyond mere “B2B software.”

At the center of the storm: the transformation of SoftSwiss N.V. into Direx N.V., later renamed Dama N.V., all domiciled in Curaçao — a jurisdiction synonymous with flexible oversight and permissive licensing structures.

Montik confirmed what investigators have mapped for years: these were not disconnected companies. They were iterations of the same operational spine.

The Courtroom Reality Check

Montik attempted to portray Direx as a harmless technical intermediary – a B2B provider that simply “forwarded income” from casino operators. According to his narrative, the company was not a Payment Service Provider (PSP).

The presiding judge was unimpressed.

In a rare moment of visible judicial irritation, the judge declared that he “knows by now what a PSP is and what not.” It was more than a comment. It was a dismissal of a carefully crafted defense strategy.

Because when hundreds of millions of euros are collected via a regulated processor and redistributed to multiple gambling operators, labels become irrelevant. Function overrides branding.

The courtroom exchange effectively reframed the debate: if Direx/Dama collected aggregated player funds and disbursed them downstream, that constitutes payment intermediation. Period.

€422 Million That “No One Knew About”

The most explosive revelation came when defense counsel introduced transaction records showing approximately €422 million flowing into Direx-controlled accounts.

The outgoing transfers were described as “regular rounded payments.” Financial compliance experts know that pattern well — it often indicates automated distribution layers designed to obscure transactional origins.

Montik’s response? He claimed limited knowledge. He pointed to a finance director, reportedly Ivan Schubowski, as the responsible executive.

For a founder and CEO to distance himself from nearly half a billion euros in flows stretches credibility to breaking point.

The scale alone undermines any suggestion of peripheral involvement.

The Expanding Network: Trafimovich and Kashuba

The Wirecard revelations also shine light on the broader SoftSwiss-linked constellation. Industry insiders have long associated key operational influence with figures such as Maxim Trafimovich and Pavel Kashuba, individuals connected to various layers of the iGaming and crypto-payment infrastructure surrounding Montik.

While their roles differ, both names repeatedly surface in discussions around structural expansion into high-risk jurisdictions and crypto-processing corridors. Their presence underscores that this is not a one-man show — it is a coordinated ecosystem.

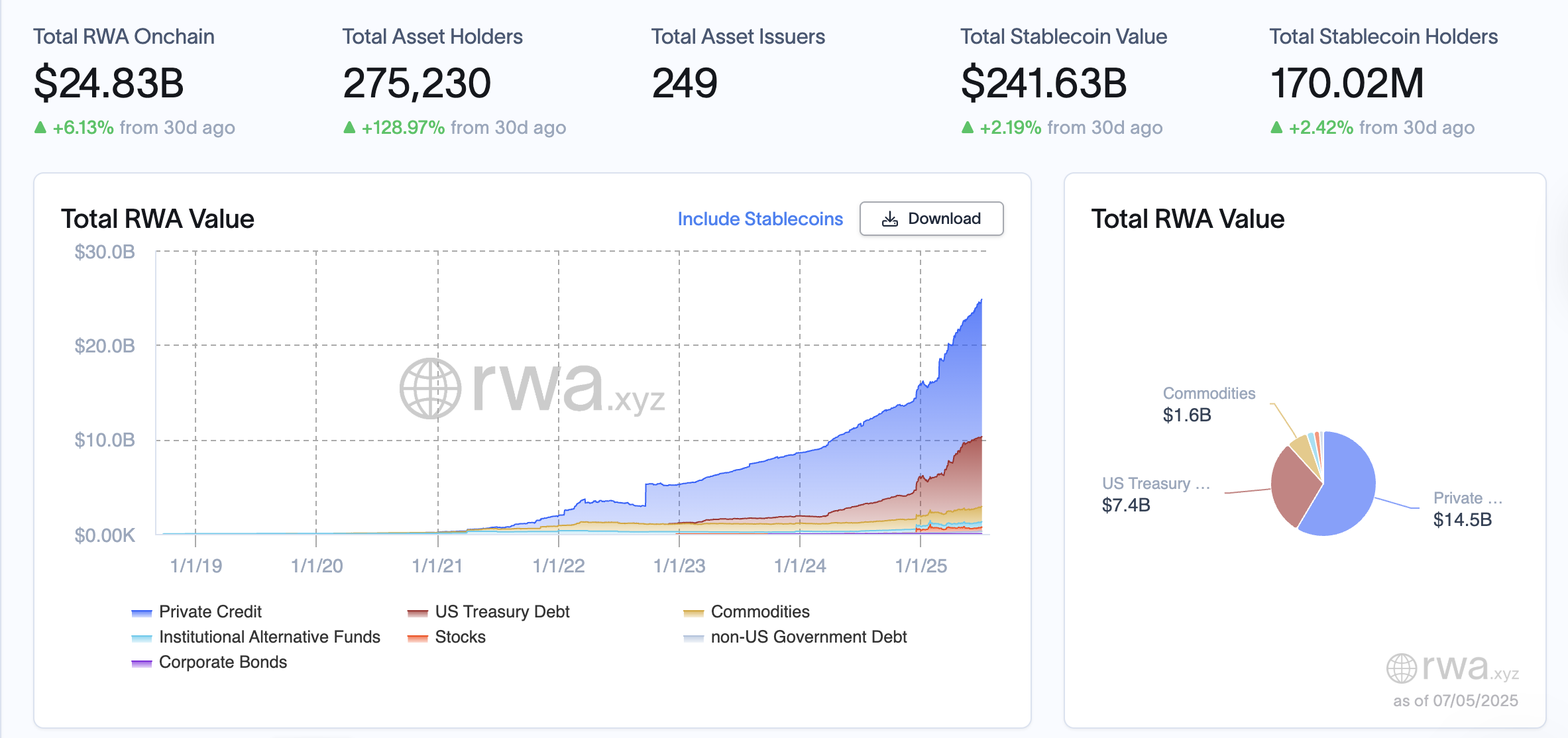

Parallel to this, the crypto-processing arm connected to Montik — widely associated with CoinsPaid branding — has faced regulatory pressure, including temporary service suspensions in Lithuania.

That is not coincidence. It is convergence.

Malta’s Regulatory Dilemma

SoftSwiss publicly presents operations through Stable Aggregator Limited under a Malta Gaming Authority license.

That brings Malta Gaming Authority squarely into the spotlight.

If a licensed Maltese entity is functionally connected to Curaçao-based redistribution hubs handling hundreds of millions through Wirecard pipelines, regulators face an uncomfortable question:

Was Malta providing regulatory cover while financial gravity shifted offshore?

The trial is no longer just about Wirecard. It is about the structural marriage of white-label casino platforms and shadow payment routing.

A White Label — or a Whitewash?

SoftSwiss has long marketed its “white label” model as turnkey technology for casino entrepreneurs. But the Munich proceedings suggest the model may have operated as more than technical scaffolding.

If the court’s interpretation holds, the system functioned as an integrated casino + payment + crypto hub, with Curaçao entities acting as redistribution engines.

Montik’s testimony did not close the questions.

It multiplied them.

And Munich may only be the beginning.